November 1, 2016

By Lisa Sturtevant, PhD

According to recent American Community Survey (ACS) data, more than one in five households in the District of Columbia is severely cost burdened, including 27 percent of renters and 12 percent of home owners. When individuals and families pay a disproportionately high share of their income on housing—50 percent or more—they often face challenges paying for other necessities, including food, health care, child care and transportation. In DC, about 60,000 households face this challenge. However, the rates of severe cost burden vary substantially for different segments of the population. Demographic characteristics like age and immigration status matter, but household income is the primary determinant of whether a household is severely cost burdened. While not surprising, this suggests opportunities for the housing industry and workforce development organizations to work together to expand housing options by both increasing the housing supply and growing incomes of residents of DC and the rest of the region.

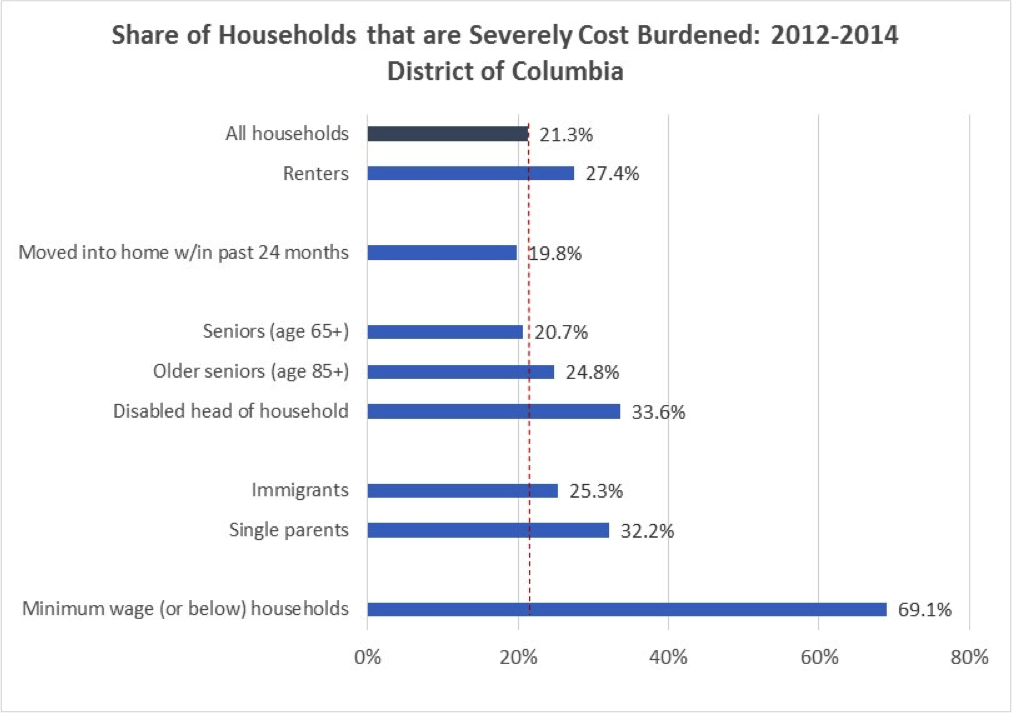

Some populations in the District are more likely than others to face affordability challenges. The rate of severely cost burdened households is higher among renters (27.4 percent) than for the overall population. While seniors age 65 or older are just about as likely as the overall population in DC to be severely cost burdened, the challenges are greater for the more vulnerable 85+ senior population (24.8 percent are severely cost burdened) and people with disabilities (33.6 percent are severely cost burdened). Single-parent families and immigrant households are also disproportionately cost burdened, with rates of severe cost burden of 32.2 percent and 25.3 percent, respectively.

But the single biggest factor that is associated with cost burden is income. Most low-income families and individuals find it difficult to find affordable housing in the District, including households with full-time workers. An individual working a full-time job at the city’s minimum wage (currently $11.50 per hour) would earn about $24,000 a year. Nearly 70 percent of households with incomes at or below this full-time minimum wage worker salary are severely cost burdened, paying half or more of that income every month towards housing costs. This group of lower-income households includes non-working households, as well, but this particular statistic is emblematic of the struggles of low-wage working households in the city and, indeed, throughout the region.

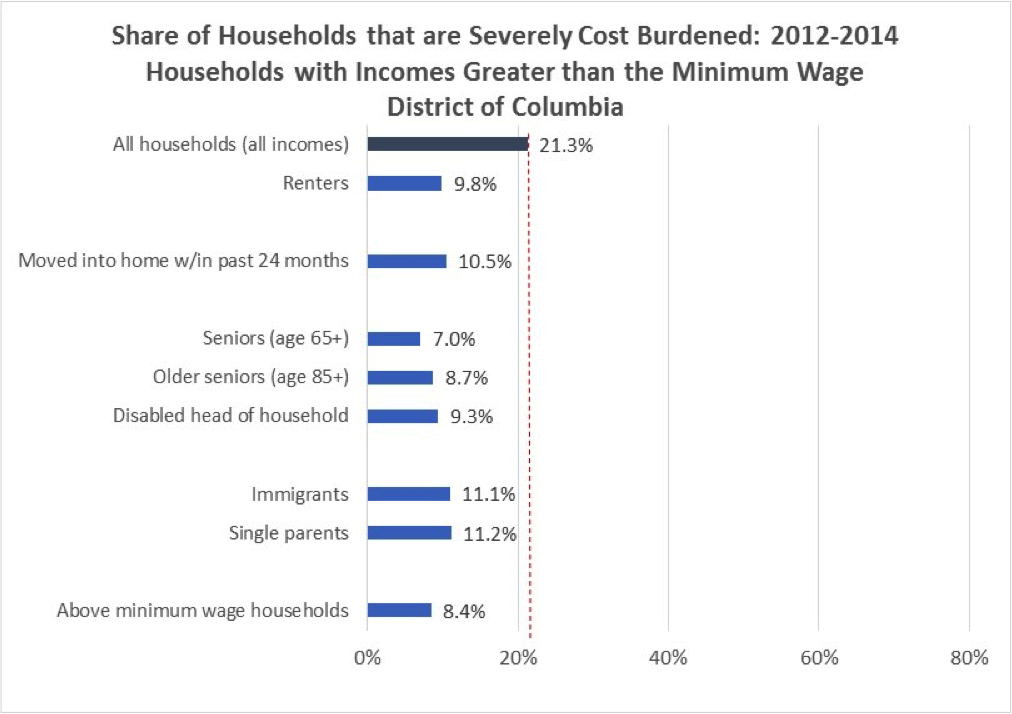

Look what happens when you examine the rates of severe cost burden only for households with incomes above the city’s minimum wage. The rates of severe cost burden are significantly lower for all groups with a household income higher than what a full-time minimum wage worker would earn in a year. About nine percent of these higher-income older seniors (age 85+) and immigrants are severely cost burdened. Among single-parents and immigrants, about 11 percent are severely cost burdened if they earn income greater than the full-time city minimum wage. These shares are dramatically lower than for the same groups that earn lower incomes.

The District of Columbia is among a growing number of states and localities that has instituted a minimum wage that is higher than the federal minimum and has planned increases. By 2020, the minimum wage in DC is set to rise to $15 per hour. A full-time, year-round worker at this wage would earn $31,200 annually. In Maryland, the statewide minimum wage increased from $8.25 to $8.75 per hour in October but in Montgomery and Prince George’s counties, the local minimum wage is $10.75 per hour. In Virginia, the minimum wage remains at the Federal level of $7.25 per hour.

Advocating for a higher minimum wage—or a living wage—in the region’s jurisdictions would help put more money in the pockets of people in lower-skill, lower-wage jobs. With more money, it could be easier for these individuals and families to find housing they can afford. However, it is possible—though by no means conclusive—that an increase in a local minimum wage could actually lead to increases in rents at the lower level. A coordinated effort of increasing wages AND expanding housing supply is the best way to ensure wage gains translate into access to more affordable housing in the city and in the wider Washington DC region. To that end, the housing industry and workforce development community should have a shared goal of working together to help alleviate the challenge for the many households living with incomes that are too low and housing costs that are too high.

With $80,000 soon to be available to first time DC homeowners, and funding for first time Maryland homeowners, it’s time to consider buying a house in the DC Metro area!

With $80,000 soon to be available to first time DC homeowners, and funding for first time Maryland homeowners, it’s time to consider buying a house in the DC Metro area! The Maryland Department of Housing and Community Development (DHCD) received 41 applications requesting $32.5 million of Rental Housing Funds (RHF) and $56.5 million of federal Low Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC) in the Fall 2016 Competitive Funding Round. Additionally, two applications include requests for a total of $3 million in Partnership Rental Housing Program funds (PRHP). The applications propose to create or rehabilitate 2,931 family, 145 senior and 453 special needs units in 15 counties and Baltimore City. Thirty four of the projects are new construction and seven are acquisition/rehabilitation projects. A complete application listing may be found

The Maryland Department of Housing and Community Development (DHCD) received 41 applications requesting $32.5 million of Rental Housing Funds (RHF) and $56.5 million of federal Low Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC) in the Fall 2016 Competitive Funding Round. Additionally, two applications include requests for a total of $3 million in Partnership Rental Housing Program funds (PRHP). The applications propose to create or rehabilitate 2,931 family, 145 senior and 453 special needs units in 15 counties and Baltimore City. Thirty four of the projects are new construction and seven are acquisition/rehabilitation projects. A complete application listing may be found