March 15, 2022

The HAND network is hard at work to address the growing housing affordability challenge across the Capital Region. Five Minutes With is a series highlighting these members and other stakeholders. This informal conversation delves into their recent projects, the affordable housing industry, and more. In honor of Women’s History Month, we are excited to share this special edition of Five Minutes With. In this edition, we had a conversation with Christy Zeitz the CEO of Fellowship Square. Check out our dialogue below to learn more about Fellowship Square’s farewell tour, Christy’s advice on how to make affordable housing projects work, and her words of wisdom for the next generation of female leaders!

The HAND network is hard at work to address the growing housing affordability challenge across the Capital Region. Five Minutes With is a series highlighting these members and other stakeholders. This informal conversation delves into their recent projects, the affordable housing industry, and more. In honor of Women’s History Month, we are excited to share this special edition of Five Minutes With. In this edition, we had a conversation with Christy Zeitz the CEO of Fellowship Square. Check out our dialogue below to learn more about Fellowship Square’s farewell tour, Christy’s advice on how to make affordable housing projects work, and her words of wisdom for the next generation of female leaders!

HAND: As CEO of Fellowship Square, you bring extensive leadership experience in management, fundraising, marketing, and program development. Can you tell us about your journey to this point?

CZ: I do my best work when interacting with others, so I’ve always sought opportunities to meet new people, learn from them, and take the next step forward in my career. Along every step along my way to my current position as CEO of Fellowship Square, I’ve proactively learned from others, embraced challenges, and worked hard to attain stretch goals. Those priorities have served me in every position I’ve ever had – across all the organizations I’ve worked with and functions that I’ve had. The guiding focus of my professional life has been to make a measurable difference in the lives of others, and this is truly the most rewarding part of my journey.

HAND: What strategic financing and collaboration strategies can you share to ensure that affordable housing providers like Fellowship Square can continue to serve vulnerable residents with dignity over the long term?

CZ: To make affordable housing projects work, it takes smart, creative people working collaboratively. Fellowship Square is one of the leading providers of affordable housing and services to low-income seniors in the region, operating 670 units and serving roughly 800 residents. We’ve put structures in place so that the rental cost is never more than 30% of a resident’s annual income – making our communities some of the most affordable in the region for seniors. The key strategies that underly our work: collaboration, creativity, and openness to new approaches. Whether for the benefit of an owner, investor, residents, or the community as a whole, there are news ideas and options that must be uncovered and teased out in some way. If we go into a project thinking we are going to do it the way we’ve always done affordable housing projects, there will be a missed opportunity somewhere. Openness to new ideas is key. We and other housing nonprofits like us have the unfortunate challenge of competing against the for-profit developers for things like land and construction costs. These costs can be staggering – and create major barriers to building more affordable housing. We must be open to new ways of thinking, new partnerships and the unexpected twists and turns that get our projects done. Sometimes the “right” approach requires writing a new playbook.

HAND: Fellowship Square has launched a “farewell tour” of the 1970’s Lake Anne Fellowship House in preparation of moving 300+ residents from the original 50-year-old building to a brand-new state-of-the-art residence across the street. Can you tell us more about this undertaking, why it’s important and any challenges you may foresee?

CZ: Lake Anne Fellowship House, originally built in 1970, was the first senior housing and first affordable housing developed in Reston. Over the past 50+ years, the property has provided housing to more than 1,300 low-income seniors. Yet the building was showing its age and upkeep of the property was exceeding the amount residents pay in rent and the subsidies received from HUD. About seven years ago, our Board decided that the best path forward was to replace the existing 240-unit building with a new facility.

This is where creativity and openness to new approaches came in. We embarked on a joint venture with Enterprise Community Development with whom we were able to craft a novel solution: instead of relocating the residents temporarily until a new building was built on the existing footprint, we would construct a new building on an underutilized portion of the current site. This would substantially reduce logistical demands as well as the number of relocations our residents would need to make. Under this creatively structured deal, once our residents are moved into the new building this spring, Fellowship Square will demolish the original building, market rate townhouses will be developed, and the land sales proceeds will be reinvested as part of the overall financing package.

Of course, financing for affordable housing is never simple. The development team needed to secure project based rental vouchers for 100% of the units and create the right mix of financing for such an ambitious goal. In addition to our partnership with ECD, financing also came from diverse arrangements with Virginia Housing and the Virginia Housing Trust Fund, Virginia Community Capital, Low-Income Housing Tax Credit equity provided through Enterprise Housing Credit Investments by Capital One, Enterprise Community Loan Fund, Fairfax County Redevelopment and Housing Authority, and, of course, HUD. In fact, much time and effort were expended convincing HUD as to the critical need to preserve the deep subsidies for the existing very low-income residents and making sure they would be eligible to move to the new building so that all residents who wished could be accommodated.

All of this was accomplished. We broke ground in 2020 (in the middle of the pandemic!) and residents will relocate this spring to the newly built Lake Anne House. The property comes with some of the best amenities, services, and environmentally sustainable features. Residents will appreciate its gym, arts room, game room, wellness clinic, beautiful outdoor terraces, wifi throughout the building and more. We will also continue to have a full time Service Coordinator onsite to serve our residents.

But the grand finale is bittersweet – for the residents who have lived at Lake Anne Fellowship House for many years, for long time staff who have worked in that building for years, and for Reston community members who have visited the property, strolled through the hallways, and visited friends and family there. This is a major change, and I know there will be some tears shed. Sometimes it’s hard to say good-bye even when a bright new future lies ahead. We have a ”farewell tour” of programs to communally and collectively celebrate our community, this building, and our memories here as we prepare for the move to the new residence.

HAND: Do you believe there is a “secret sauce” to addressing housing affordability and creating more equitable communities in our region? If so, what do you think that is? What do you think is the largest obstacle?

CZ: There’s no “secret sauce” to housing affordability. In my mind, it’s more like a “Las Vegas buffet” of options, opportunities, considerations, and collaborations – and the plate for each region may be filled quite a bit differently. In the Washington DC Metro area, our housing needs span the spectrum of price points, amenities, services, and financing. The affordability factor is a core fundamental part of supporting the local workforce. As such, creating more affordable housing has to be a community effort – it can’t just be left to the housing advocates to fight for. The community as a whole has to come together to embrace housing affordability for all. The more collaborators at the table, the more varied our buffet of options and the more success we can have.

The type of affordable housing will vary community to community, but collaboration across organizations will always be key. For example, very low-income residents, especially those below 30% AMI, require significant subsidies. Beyond rental assistance, this often includes the need for the provision of services including transportation, healthcare, food assistance, healthcare, mental health services, and more. This means that affordable housing management must also be able to access public and private resources to augment standard housing management activities. Fellowship Square accomplishes this by building a deep network of resources within our local community to plug into. Our vulnerable residents can access care managers who can provide or refer the residents to appropriate services in our community. This is important to build and foster.

HAND: In March we celebrate Women’s History Month and International Women’s Day. Given your extensive leadership experience, what advice would you give to the next generation of female leaders? What do you think is the most significant barrier to female leadership, and how have you overcome those barriers?

CZ: Few things make me prouder than to see young women asserting themselves and stepping up when they have an opportunity to lead. There are so many valuable traits and perspectives that we all benefit from when women are in leadership positions. For today’s emerging female leaders, they cannot sit by and wait to be asked to lead – it’s much more important that they seek out and even create those opportunities.

Sometimes the biggest barrier to reaching the next level in our careers is how we hinder ourselves. Whether through self-doubt or even other commitments, it comes down to priorities and having a vision for our own professional futures. Nothing will be handed to us on a silver platter – nor should it. Working hard and getting ahead is where you learn to grind it out and become a true inspirational leader. Leadership comes from experience, it comes from perspective, and those both come from hard work. But hard work that results in great leadership cannot be achieved in the shadows!

Women must always put themselves at the table – and in my experience, there’s always a way to have your voice heard in those circles, whether directly or indirectly. Regardless of someone’s position on a staff flowchart, each individual person can be a leader in some respect. Young women who may feel they aren’t in a position of leadership can still have an important impact on the trajectory of projects, assignments, teams, and workplace culture. Show initiative and you will be rewarded.

As you can tell, I’m very much an optimist. I always believe that what I want to happen can happen, it’s up to me to figure out how to make it happen. And the only thing holding me back is my own ideas of what I can and cannot accomplish. I hope other women can learn from this.

HAND: What is your “why”? What keeps you motivated to continue your work in this space?

CZ: Working in the affordable housing space is a little like making dreams come true. For too many people today, having a safe, affordable, and stable home can seem out of reach. Being a part of helping to make this dream of housing happen is a daily motivator for me. Nearly every week, I get at least one call from one of our 800+ residents who wants to tell me about what’s going on in their life. They never hesitate to say how thankful they are that they live at Fellowship House. This is what keeps me motivated every day. I am so proud of the work my organization does, and really appreciate the time and effort the Board and staff put into our mission.

HAND: If you weren’t working in this industry, what might you be doing?

CZ: I’d be living in the Caribbean, working on my side hustle as a fiction writer…and helping anyone who asked!

The HAND network is hard at work to address the growing housing affordability challenge across the Capital Region. Five Minutes With is a series highlighting these members and other stakeholders. This informal conversation delves into their recent projects, the affordable housing industry, and more. In this edition, we had a conversation with Ronette “Ronnie” Slamin, founder of Embolden Real Estate. Check out our dialogue below to learn about her development firm, what she believes women leaders of color in the real estate industry can do to move the needle in a different direction, and the importance of explaining the multiple levels of housing affordability.

The HAND network is hard at work to address the growing housing affordability challenge across the Capital Region. Five Minutes With is a series highlighting these members and other stakeholders. This informal conversation delves into their recent projects, the affordable housing industry, and more. In this edition, we had a conversation with Ronette “Ronnie” Slamin, founder of Embolden Real Estate. Check out our dialogue below to learn about her development firm, what she believes women leaders of color in the real estate industry can do to move the needle in a different direction, and the importance of explaining the multiple levels of housing affordability. The HAND network is hard at work to address the growing housing affordability challenge across the Capital Region. Five Minutes With is a series highlighting these members and other stakeholders. This informal conversation delves into their recent projects, the affordable housing industry, and more. In honor of Women’s History Month, we are excited to share this special edition of Five Minutes With. In this edition, we had a conversation with Christy Zeitz

The HAND network is hard at work to address the growing housing affordability challenge across the Capital Region. Five Minutes With is a series highlighting these members and other stakeholders. This informal conversation delves into their recent projects, the affordable housing industry, and more. In honor of Women’s History Month, we are excited to share this special edition of Five Minutes With. In this edition, we had a conversation with Christy Zeitz  The HAND network is hard at work to address the growing housing affordability challenge across the Capital Region. Five Minutes With is a series highlighting these members and other stakeholders. This informal conversation delves into their recent projects, the affordable housing industry, and more. In this edition, we had a conversation with

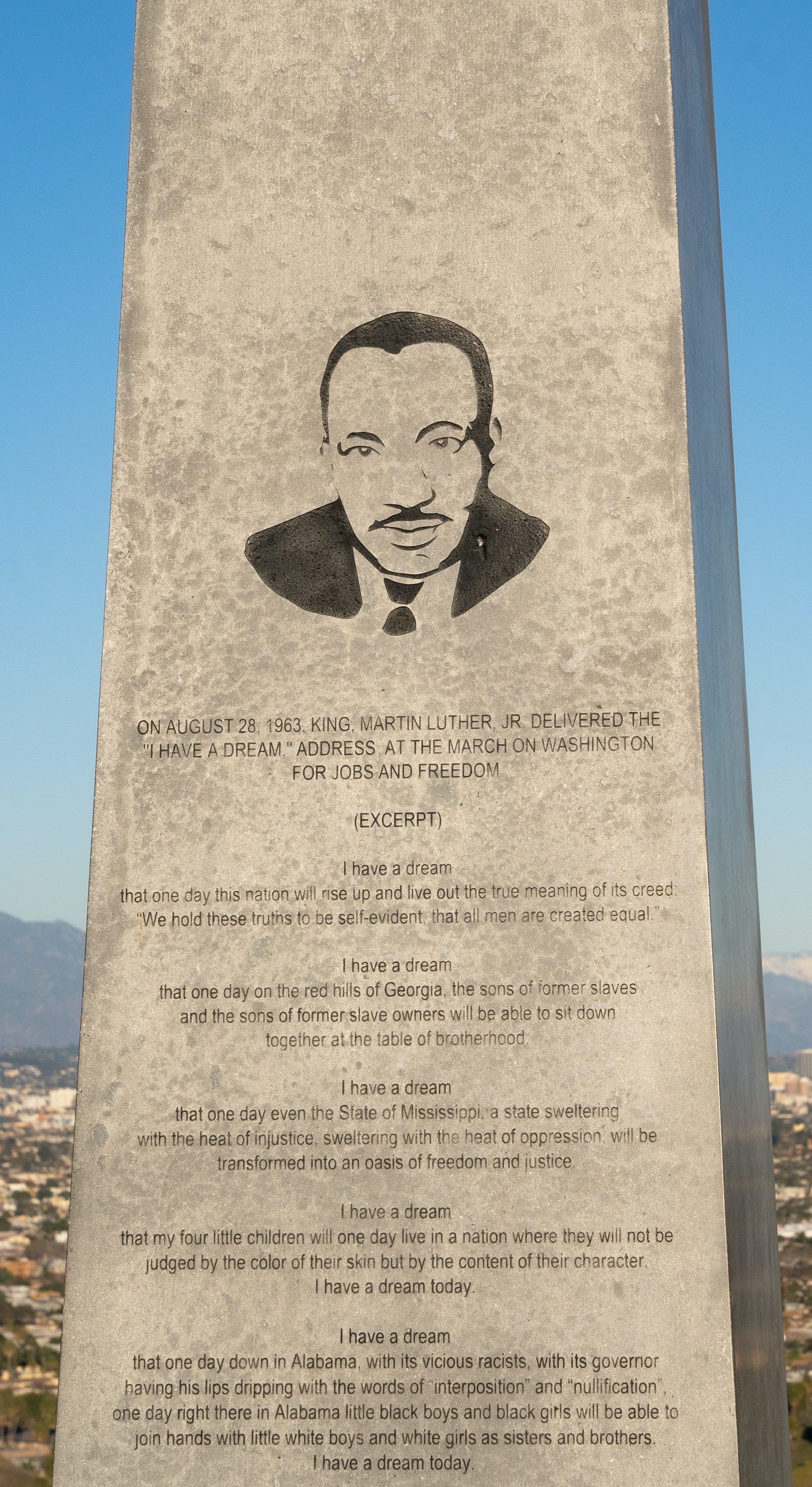

The HAND network is hard at work to address the growing housing affordability challenge across the Capital Region. Five Minutes With is a series highlighting these members and other stakeholders. This informal conversation delves into their recent projects, the affordable housing industry, and more. In this edition, we had a conversation with  On Monday, January 17, 2022 we commemorated the birthday, life, and work of one of the most prominent African-American civil rights activists, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Many remember King as a Civil Rights Movement leader, but fewer are familiar with the role he played in the fair housing movement. During King’s time, black Americans were systematically excluded from living in certain areas. This process of redlining relegated black people to low-income areas with poor quality housing. In his role as a Civil Rights leader, King recognized that housing was a core component of racial injustice in the United States and decided to take action!

On Monday, January 17, 2022 we commemorated the birthday, life, and work of one of the most prominent African-American civil rights activists, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Many remember King as a Civil Rights Movement leader, but fewer are familiar with the role he played in the fair housing movement. During King’s time, black Americans were systematically excluded from living in certain areas. This process of redlining relegated black people to low-income areas with poor quality housing. In his role as a Civil Rights leader, King recognized that housing was a core component of racial injustice in the United States and decided to take action!

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought more attention to the field of public health. Every day, people are seeing and hearing from epidemiologists, clinicians, laboratory scientists, researchers and more. While the spotlight is on the field, we should seize this moment to bring national attention to our greatest imperative: reducing health disparities and advancing

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought more attention to the field of public health. Every day, people are seeing and hearing from epidemiologists, clinicians, laboratory scientists, researchers and more. While the spotlight is on the field, we should seize this moment to bring national attention to our greatest imperative: reducing health disparities and advancing