The Impact of Sequestration on the Washington DC Area Housing Market: How Across-the-Board Federal Spending Cuts Restructured the Region’s Economy and Will Alter Demand for Housing

By Lisa A. Sturtevant, PhD

The federal budget cuts known as sequestration reduced overall discretionary spending and placed budget caps on total defense and non-defense spending. Introduced as part of the Budget Control Act of 2011, these across-the-board spending cuts were put into place as of March 1, 2013. Legislation passed in 2013 lifted the spending caps through fiscal year 2015 but the caps will return in fiscal year 2016 unless Congress acts.

The federal budget cuts known as sequestration reduced overall discretionary spending and placed budget caps on total defense and non-defense spending. Introduced as part of the Budget Control Act of 2011, these across-the-board spending cuts were put into place as of March 1, 2013. Legislation passed in 2013 lifted the spending caps through fiscal year 2015 but the caps will return in fiscal year 2016 unless Congress acts.

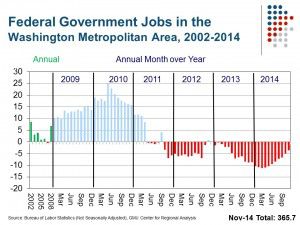

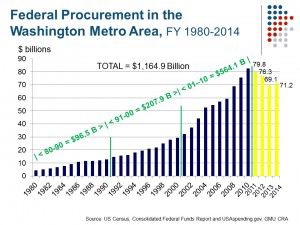

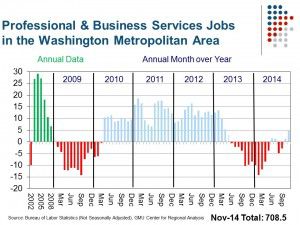

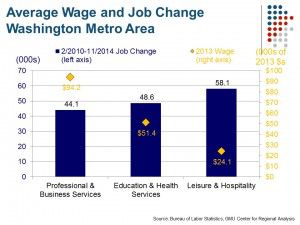

While the impacts of sequestration were widespread, the greater Washington DC area was particularly hard hit by the cuts because of our economy’s dependence on the federal government. Federal government employment in the region has declined steadily since the end of  2011. Federal procurement spending—which had escalated over the past three decades—declined for three consecutive years before upticking slightly in 2014. Procurement spending supports many professional and business service jobs in the region, and that sector has taken a hit. As a result of job losses in the government and professional and business services sector, average wages have declined across the region as we have traded higher wage jobs for lower wage jobs during the recovery.

2011. Federal procurement spending—which had escalated over the past three decades—declined for three consecutive years before upticking slightly in 2014. Procurement spending supports many professional and business service jobs in the region, and that sector has taken a hit. As a result of job losses in the government and professional and business services sector, average wages have declined across the region as we have traded higher wage jobs for lower wage jobs during the recovery.

The effects of sequestration are not likely temporary. Sequestration has fundamental reset the regional economy. According to estimate from the George Mason University Center for Regional Analysis, the federal government’s portion of the region’s economy will decline from about 40 percent today to just 29 percent by 2019.

The effects of sequestration are not likely temporary. Sequestration has fundamental reset the regional economy. According to estimate from the George Mason University Center for Regional Analysis, the federal government’s portion of the region’s economy will decline from about 40 percent today to just 29 percent by 2019.

The regional economy will need to diversify moving forward. Local jurisdictions across the region are planning for how to attract new businesses to a new regional economy. The Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments has just launched an initiative on regional economic competitiveness. Thus, there is recognition that things are changing in the region. Moving forward, the region will see higher growth in the health, leisure and hospitality and other services sectors.

These jobs will come with lower wages than what we’ve become used to when the federal government and professional and business service sectors were the primary drivers of job growth.

These jobs will come with lower wages than what we’ve become used to when the federal government and professional and business service sectors were the primary drivers of job growth.

What are the implications for the region’s housing market?

Despite some selected positive indicators around the region’s for-sale housing market in early 2015, there is growing evidence of a general slowdown in the market in response to slower overall regional job growth. And the lower wages and household incomes associated with economic restructuring in the region are evident in the housing market activity data broken down by price point; the fastest selling, most in-demand homes have been among lower priced homes. We will likely see a slowdown in price appreciation across the region in the coming year, and inventories of lower-priced homes will continue to be limited.

While changes at the federal level will make access to homeownership easier for many, demand for rental housing will continue to be strong in the region in the new economy. As a result of the economic restructuring brought on by sequestration, there will be a greater need to serve households lower down the income spectrum, as well as to serve larger households, including families that may be renters by necessity.

The Washington DC region has been very effective at producing high end rental housing. More than half of all building permits issued in the region last year were for units in multifamily buildings and the rents in those new building have topped over $2,000—or more—for a one-bedroom unit. The rapid increase in rental supply at the higher end was not coupled with similar increases in production at the lower end of the housing market. According to a recent report from the DC  Fiscal Policy Institute, since 2002, the District of Columbia lost nearly half of all units renting for less than $800 per month. The study authors concluded that there is virtually no market-rate housing in the city affordable to low-income households; all housing renting for below $800 per month is subsidized housing.

Fiscal Policy Institute, since 2002, the District of Columbia lost nearly half of all units renting for less than $800 per month. The study authors concluded that there is virtually no market-rate housing in the city affordable to low-income households; all housing renting for below $800 per month is subsidized housing.

There is some evidence, however, that the market is beginning to respond to the demand for lower-cost rental housing. Or that there will be a slowdown, at the very least, in targeting new construction at the very high end of the market. A recent Washington Post article documented discounts, free rent, and other incentives owners of new multifamily buildings have had to offer to potential renters to get them to sign a lease. An oversupply of rental housing across the region—from DC to Tysons to Rockville—suggests that builders have overbuilt for the high-end market, a population whose growth has slowed as a result of the new economic reality in the region. Greater demand for more moderately-priced rental homes may lead to more diverse construction, including more homes affordable to renters further down the income spectrum. High land costs, however, may mean that the majority of this new construction will occur outside the region’s urban core.

Last year, in addition to targeting the higher end of the market, developers of multifamily rental properties also targeted aggressively single Millennials. Family-sized units have been notoriously hard to come by in the region. But there will be growing demand for larger, multifamily units in the region in the years ahead. As members of the region’s Millennial population age—and marry and have children—some may seek to remain in high-density more urban environments where they will need rental or multifamily housing with two or three bedrooms. At the same time, the region’s population will continue to become more racially and ethnically diverse. Since non-white households tend to be larger, there will be additional needs for larger multifamily rental housing. And even as the economy continues to recovery and wages slowly start to rise, many workers will still be looking for housing where they can split rent, which means additional demand for two and three bedroom units.

Community opposition to multifamily rental housing is common, and NIMBYism around multifamily buildings with large, family-sized units can derail a project. Understanding the fiscal and other concerns residents have—and learning how to communicate effectively to combat this NIMBYism—will be critical for ensuring that this needed housing gets built.

The region’s new economy means shifting housing demand. The market will respond to some aspects of changing housing demand, but as the DC Fiscal Policy Institute and other local jurisdictions have shown, new supply has not been able to outpace losses in market-rate affordable housing. In order to ensure that workers in the new regional economy can find housing they can afford, we will need continued subsidies to meet housing needs for the lowest-income workers and land use and regulatory strategies to incentivize the production of housing affordable all along the income spectrum and for households of different sizes and types.

Next month: Prospects for Regionalism

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!